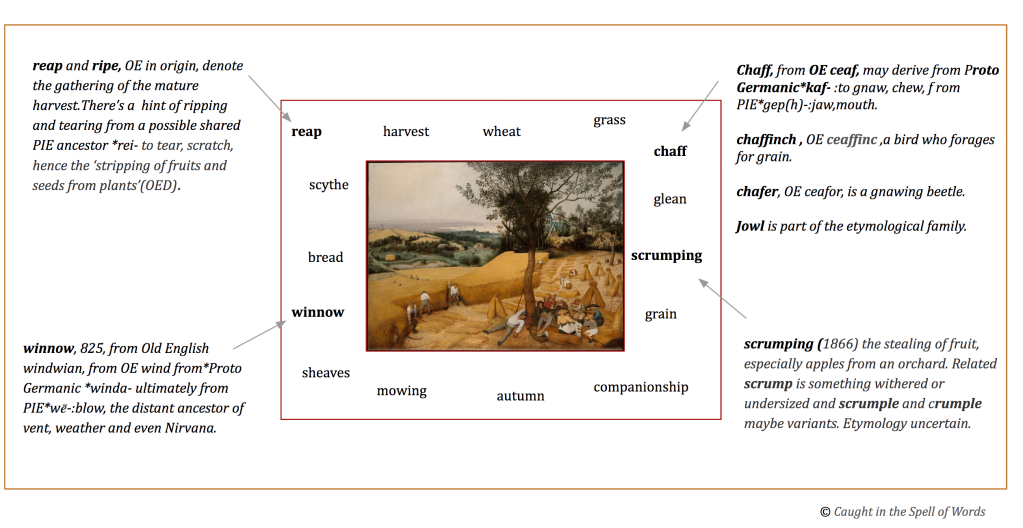

Above The Harvest, Pieter Breugel the Elder, 1565.

Perhaps because there have been a series of damp, rainy, winter mornings here where I live, I am enthralled by this painting. In Breugel’s fields the day is hot and sticky. In the foreground a man sprawls out for a nap, a reprieve from the mowing. A group of harvesters eat and laugh under the shade of a tree. One stretches behind to cut a slice of cheese. A woman with a shirt the colour of the ripened wheat sits upright rather carefully eating her bread. I love this golden hued painting and the way it gives a glimpse into summers and country life of the sixteenth century.

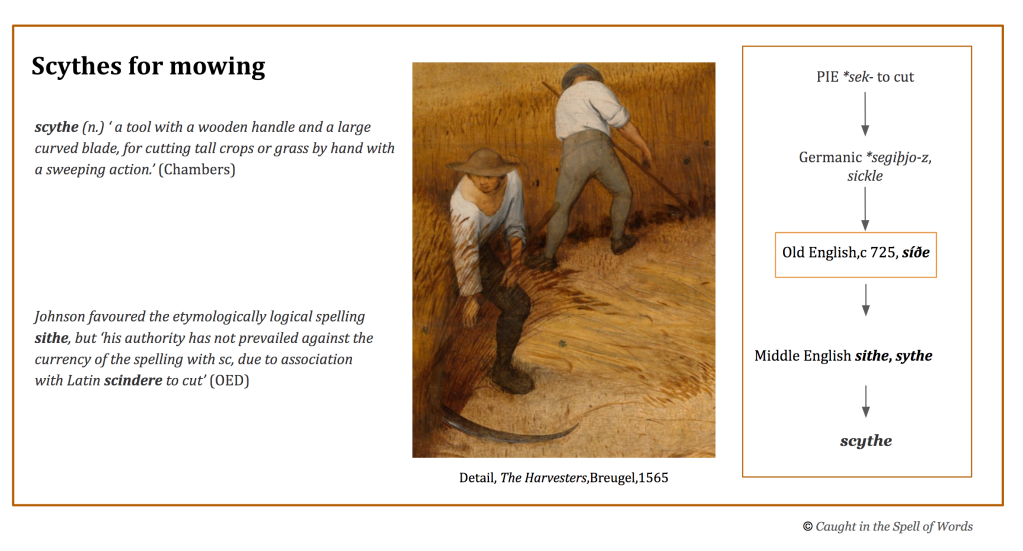

I like to play a sort of spot the difference, spot the similarity game observing what’s not so frequent and what remains today. The haystacks for a start are different in my part of the world, not in ricks or mounds, rarely now in square bales; today bales rolled like giant roulades lie fatly in paddocks. Clothes too are different and the swing and hissing sweep of the scythe as it cuts through the crop is now replaced by machinery and its mechanical roar.

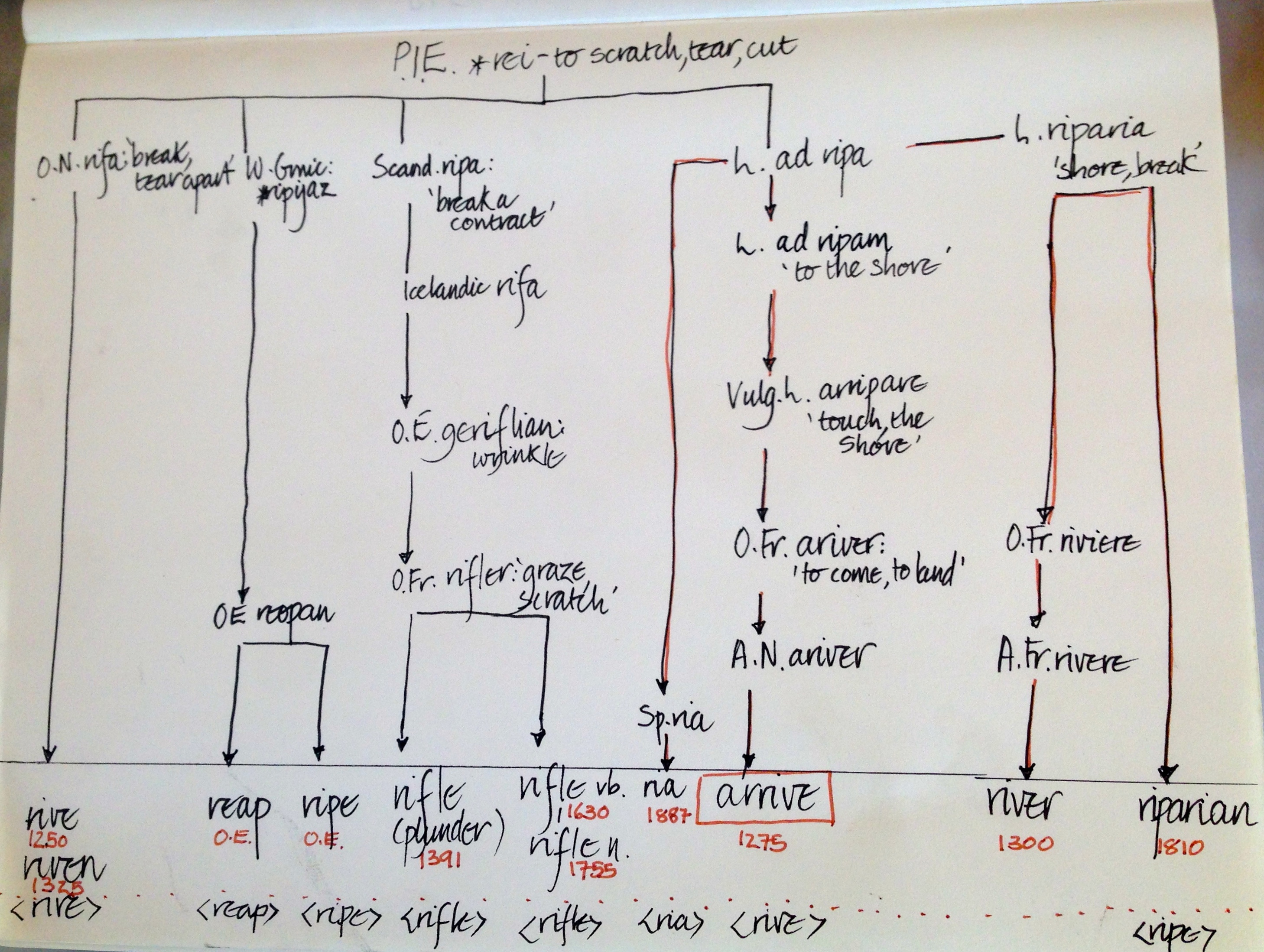

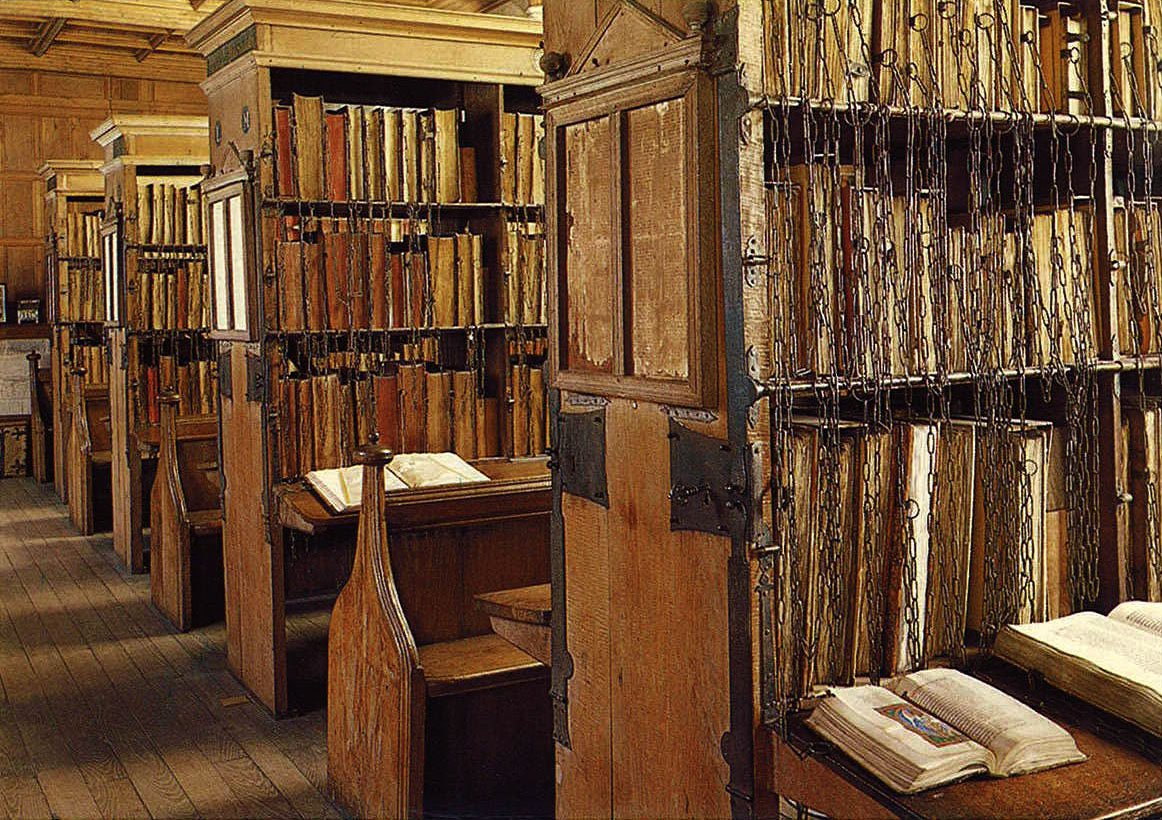

Yet hard work, laughter and eating in companionship remain. There’s so much to see in this landscape– someone up a tree shaking down pears, women below gathering them, women carrying wheat sheaves in the middle ground, and in the distance monks swimming in a pond, beyond children play and further in the distance, sailing ships glide in the harbour. This painting is of the everyday, but no longer our typical summer’s day; it’s a celebration of harvest, of growing and reaping, of summers and the cycle of the seasons. Inevitably, it’s words provoked from this painting that flood my mind and have me contemplating their relatives. As always, this orthographic research becomes a window into our past where one word leads to another.

In the foreground to the left, reapers mow the crop with scythes. Scythe and its distant ancestor, the Proto Indo European root *sek- to cut, is the shared ancestral source of other cutting implements such as saws, hacksaws and secateurs. Even sedge,OE secg, the spiky, cutting grass, is a distant relative. So Germanic saw, scythe, sedge and Latinate secateurs are etymological relatives. Their base elements differ indicating that while etymologically related, they belong to separate morphological families.

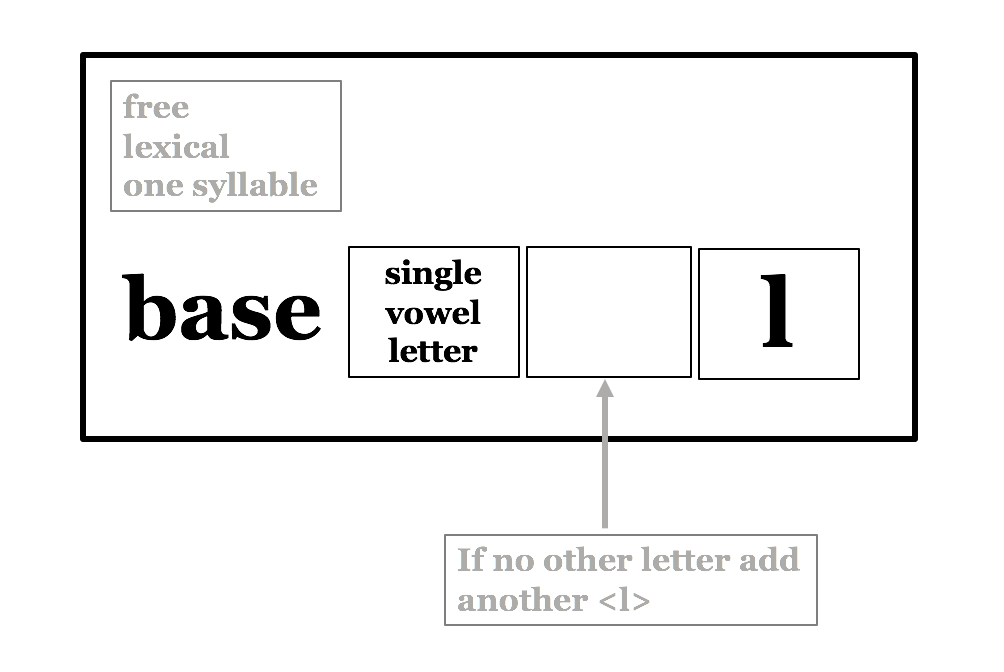

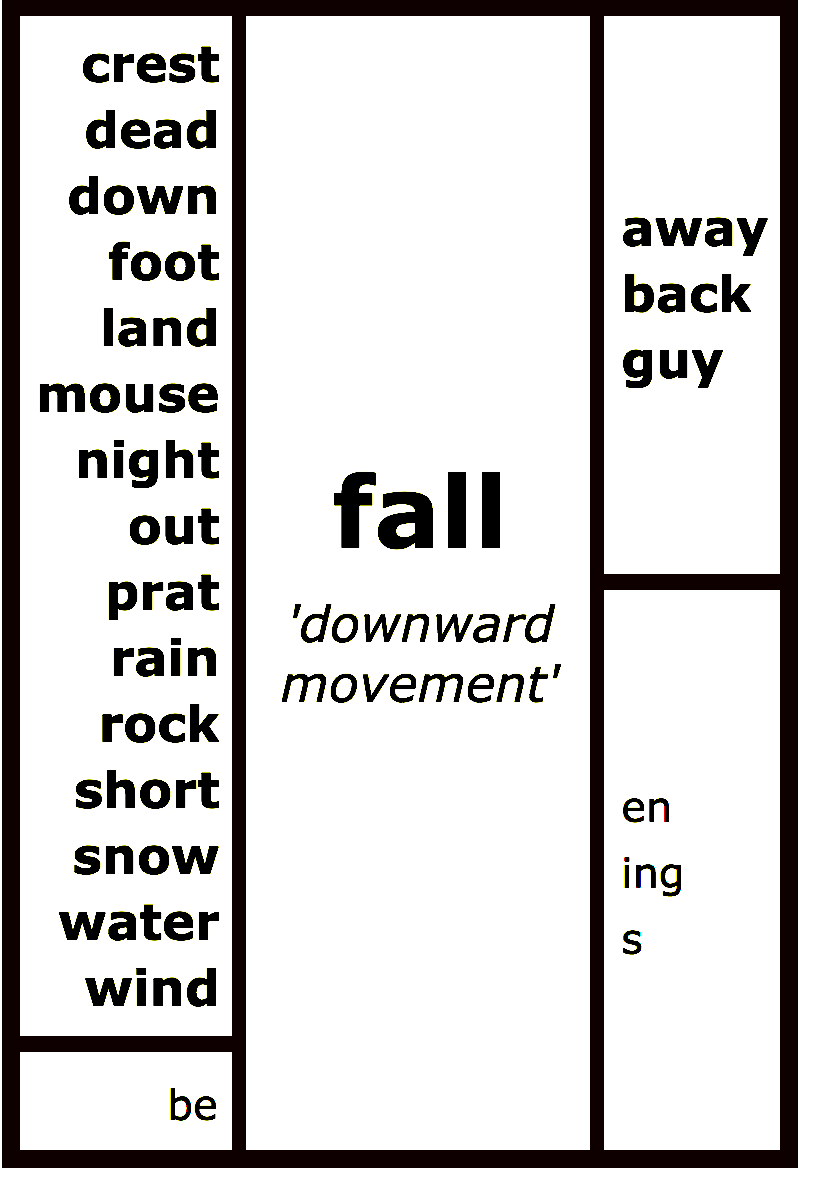

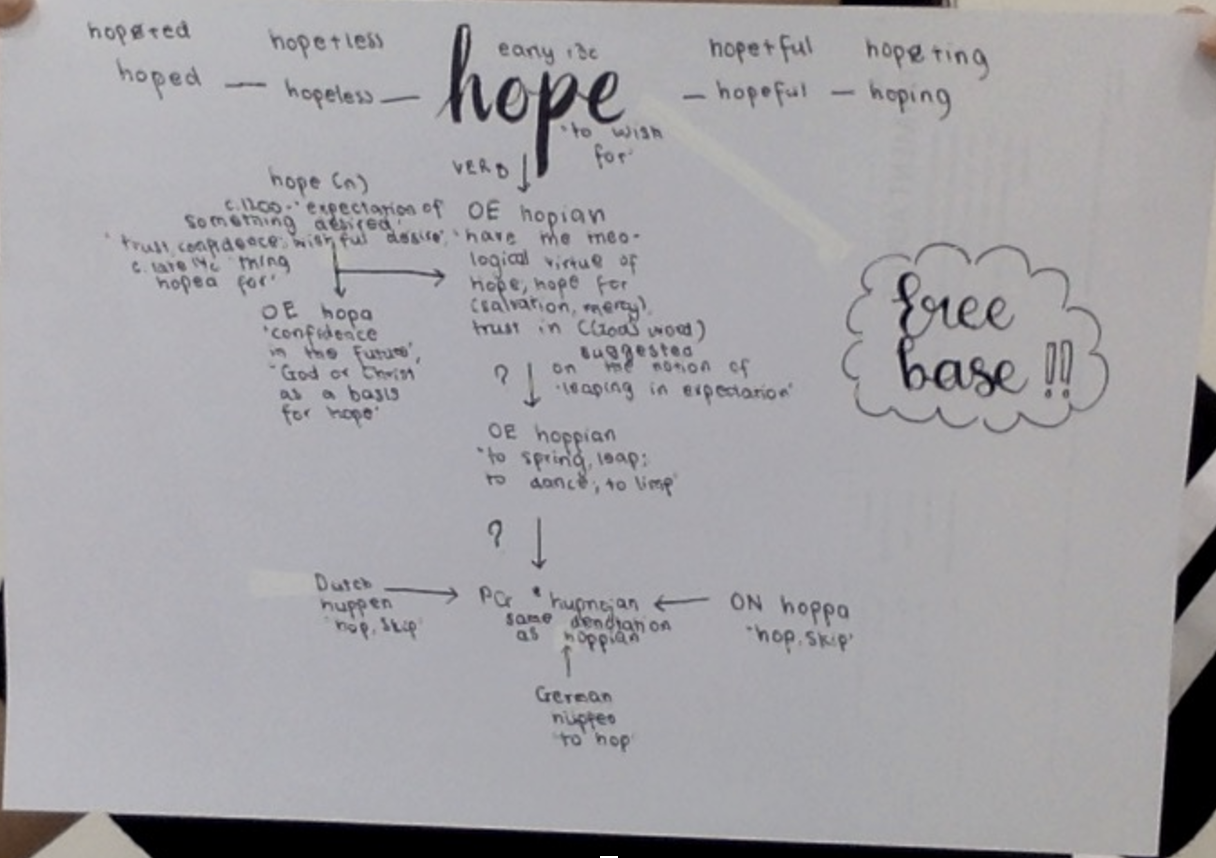

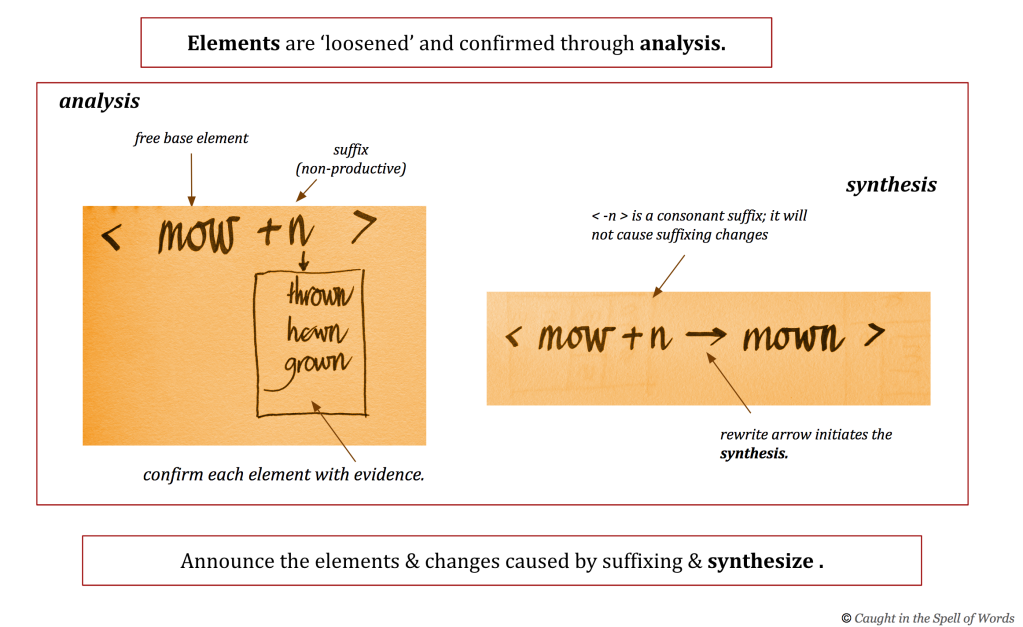

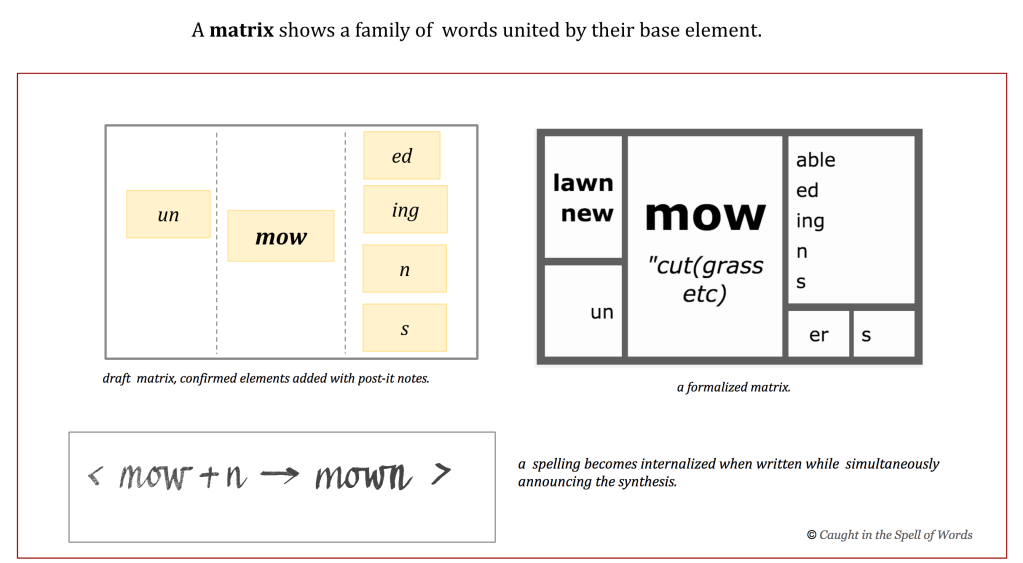

I contemplate the harvesters and their mowing. Mow is a free base element with a small morphological family.

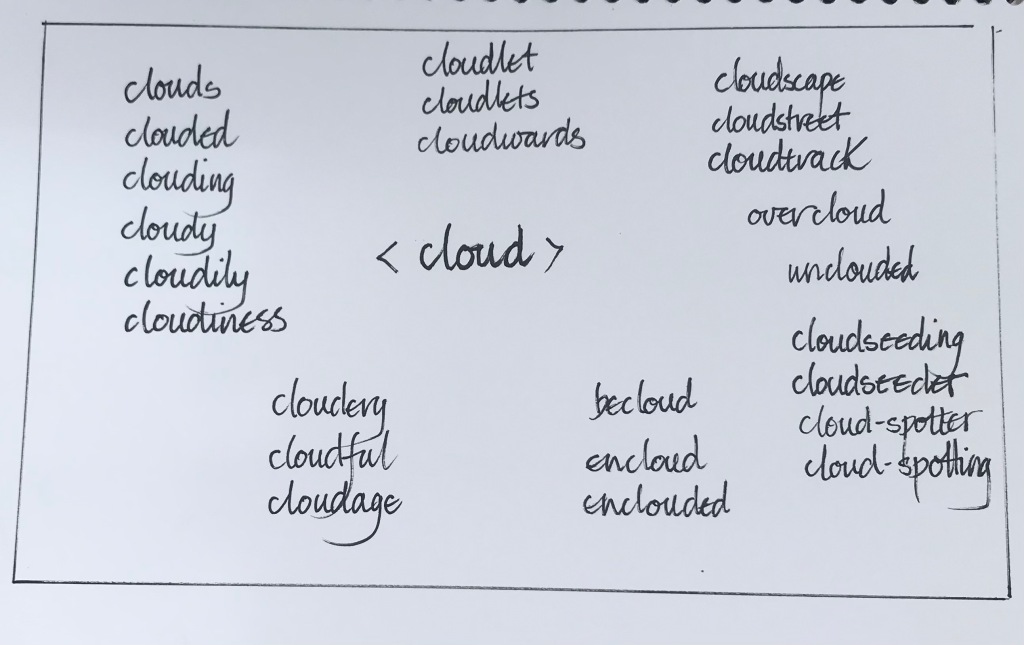

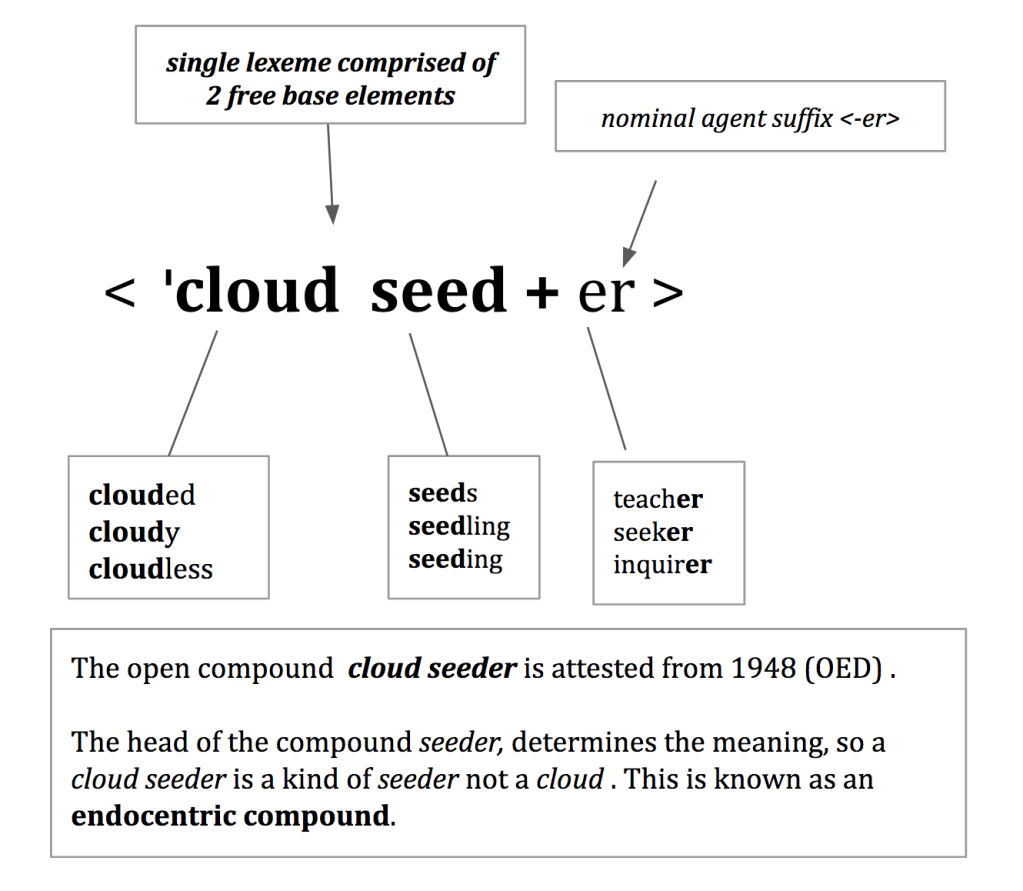

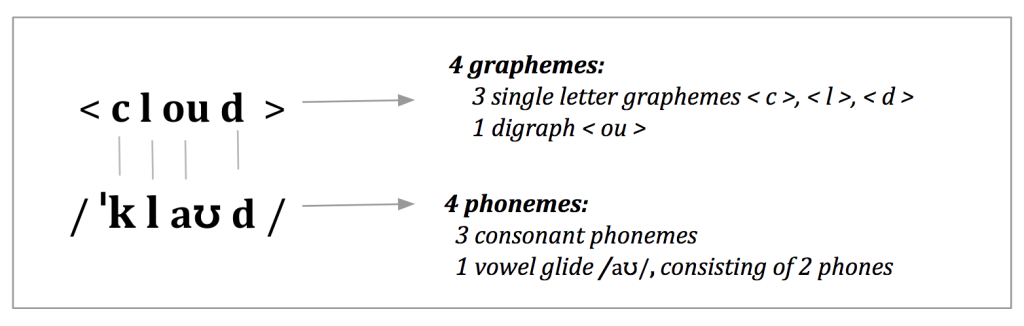

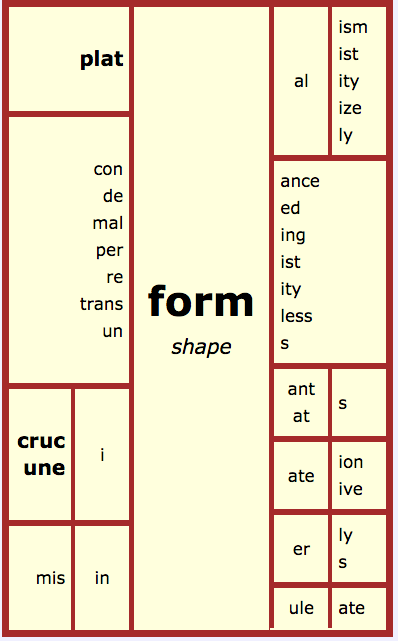

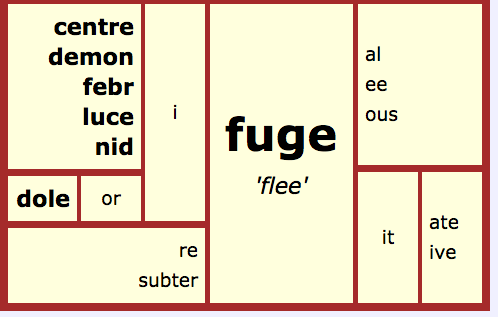

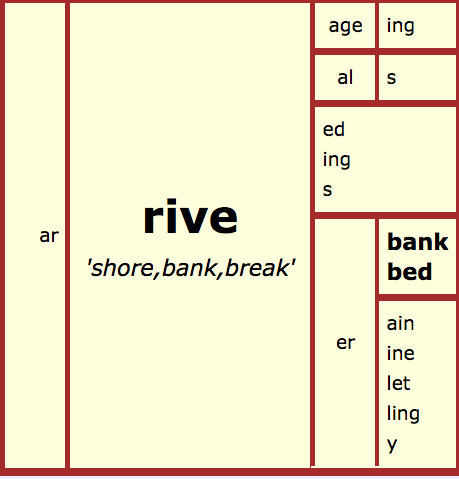

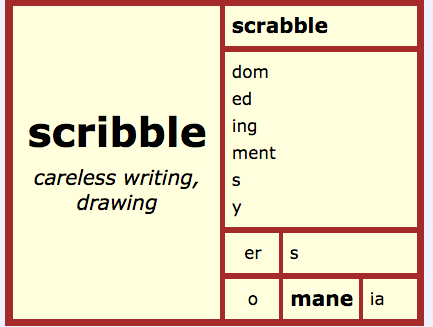

Words belong to families and gathering potential relatives in a web, before rushing helter-skelter to dictionaries, provides evidence to contemplate when analyzing. Analysis loosens a word into its elements where each element is considered and justified. Analysis exposes the base element, the heart of the family. Therefore, the proposal of the underlying elements laid out in an algorithm, like any truth, cannot be thoughtfully considered on the basis of a single word. Analysis, hand in hand with a proposed web of morphological relatives, forms an hypothesis for a base element that is supported or rejected when examining the etymology.

Elements as they are confirmed can be placed in a matrix for further consideration of the morphological family.

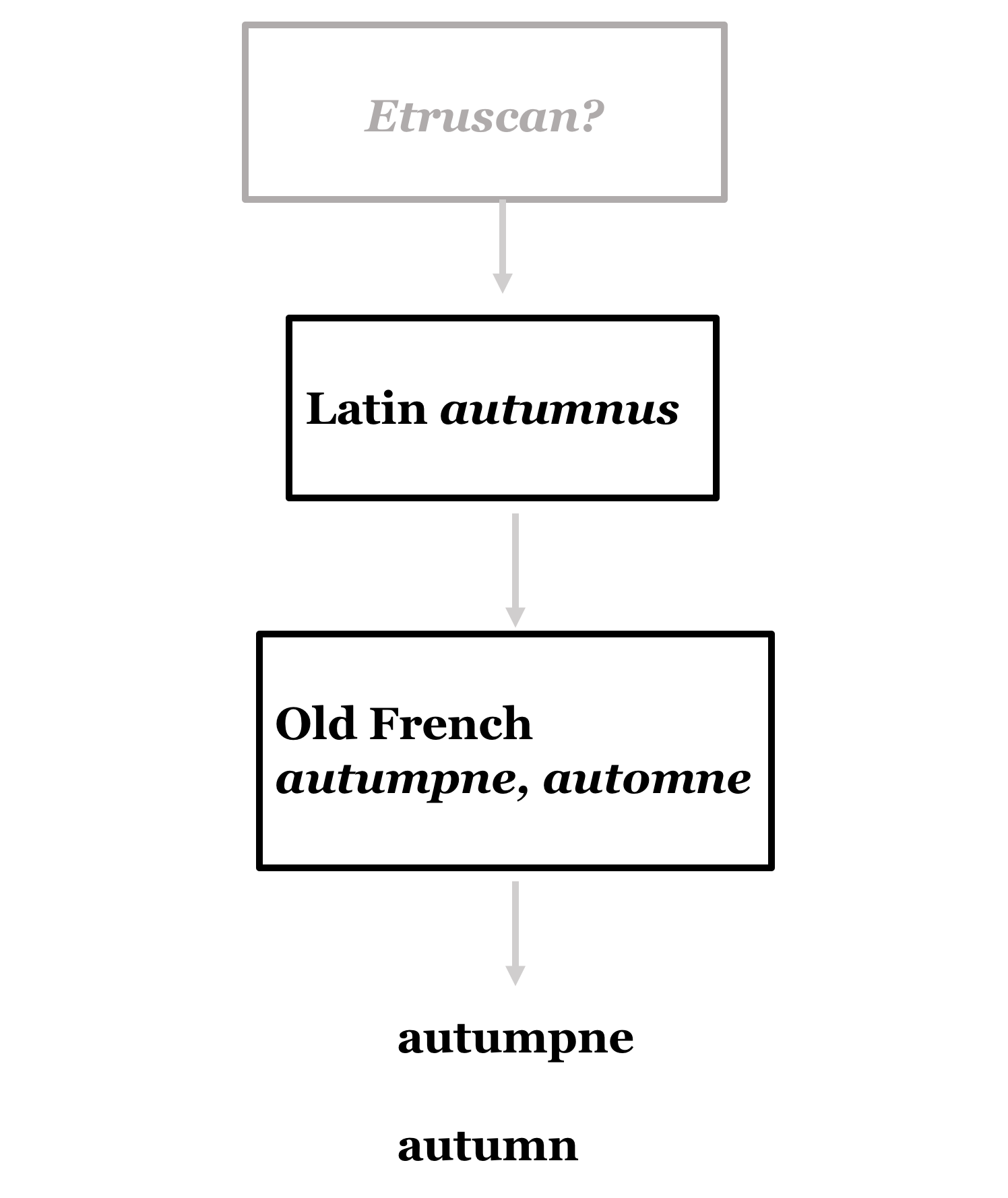

Mow is of Germanic origins as you’d expect from a centuries old agrarian task. Attested in early Old English, the etymon mawan is “to cut (grass, etc.) with a scythe or other sharp instrument”. Remove the Old English suffix <-an> from mawan and you see the resemblance to present day mow. The Old English etymon can be traced further back to a Proto Indo European root *mē- to cut down grass or grain, the ancestor of math and meadow and distant relatives of mow.

Mow has accrued several senses over time with a figurative sense from 1300 onwards: ‘To cut down (a person) in battle with a sweeping stroke like that of a scythe; to destroy or kill indiscriminately or in great numbers; (also) to kill with a hail or fusillade of shots. : Now usually with down; spec. to knock (a person) down with a car or other vehicle’.(OED)

Mow as a cricketing term is from 1844 onwards: ‘To hit (the ball) to leg with an unorthodox sweeping stroke‘(OED)

Once the base element is established, its boundaries clear, then the graphemes building the base can be examined. The digraph <ow> occurs in the initial, medial, and final position of a base element : owl, crown, howl, cow. Yet when the digraph represents /əʊ/ as in mow /məʊ/ the digraph is frequently located in the final position. I have found very few words where it occurs initially, only Germanic: owe and its relative own. The words with the digraph signalling /əʊ/ are overwhelmingly Germanic in origin, such as: yellow, swallow, mellow, crow, know, blow.

Etymological relatives

The etymological relatives derived from the ancestral PIE root *me-(4)‘to cut down grass or grain’ too are interesting.

Aftermath: Who would have thought a word that has come to be familiar as the ‘an unwelcome consequence or effect'(OED), result of a catastrophe, or unpleasant circumstance has its origins in harvesting and in particular, mowing? Aftermath is complex, a compound composed of two free base elements: <after + math>. The noun aftermath, attested 1496, is the second crop of the season, the crop occurring after the earlier one has been harvested or ‘mown’. Aftermath was used figuratively early on, but from 1600s it took on negative connotations as ‘a period or state of affairs following a significant event, esp. when that event is destructive or harmful.’ to ‘an unwelcome consequence or effect’ (OED)

The base element <math> is a free base element, albeit rare. It has derived from the Old English noun mæð : mowing. This derives from the same ancient Proto Indo European root: *me– as Old English:mæd “meadow”. So mead, meadow, mow, aftermath, all etymologically related and redolent with a grassy scent of harvests.

Today we can still find math present in the agricultural compounds:

undermath 1881: ‘An undergrowth of grass’.

lattermath, 1510,’ A second or subsequent crop of hay or new growth of grass, after the first has been mown.'(OED)

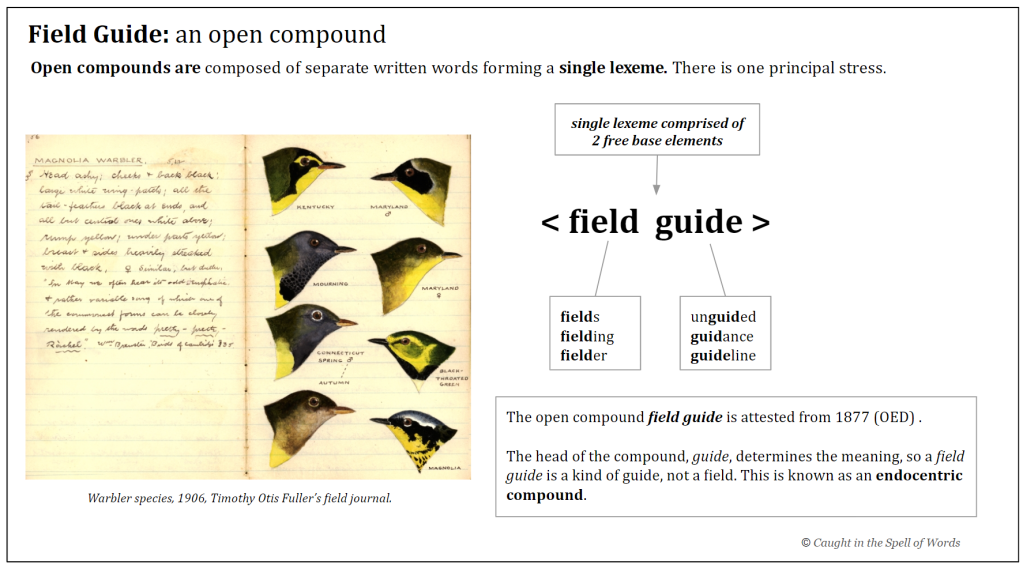

The expression day’s math, is an open compound attested 1559: ‘ An area of land that can be mown by one person in a day, often taken as approximating to an acre; a day’s mowing; (more loosely) a small portion of land.’ (OED)

Although the base element <math> is attested in compounds, the OED notes that today math ‘is not found as a simplex in Middle English except in the place name Le Mathes in Cambridgeshire (1221; also as the second element in compound place names (e.g. Wetemathis (1302), now Wheatmath Field, Cambridgeshire).

I’m also entranced by several of the synonyms for aftermath, many faded from the language or lurking only in dialects :

edgrew attested 1440 ‘the aftergrowth of grass’. The <ed-> was once a prefix, frequent in Old English but on the wane in the Middle English period.

eddish of 1460, ‘grass (also clover, etc.) which grows again; an aftergrowth of grass after mowing’. It’s etymology is vague:perhaps Old English edisc: park or enclosed pasture or perhaps a base element <ed > with a sense of again.

fog, attested 1570, is surprising, not the damp, misty variety, but ‘a second crop of grass which grows after hay has been mown or harvested.’ (OED) Ironically this fog is foggy,its etymology vague – probably derived from a Scandinavian etymon -a Norwegian cognate fogg :’ long-stalked, weak, scattered grass or heather’.

When fossicking through the dictionary in pursuit of ‘mow’, I was surprised to find several other less familiar mows lingering in English. Mow , the noun, is attested early in Old English as múga, múha, múwa: ‘A mow (as in barley- mow), a heap (of hay, corn).(Boswoth-Toller Dictionary) Although semantically connected with hay, it is not related etymologically. Rather its denotation is of piles and heaps and therefore crowds of people. Nominal mow has cognates in Old Icelandic múgi swathe, crowd, and further cognates in Old Swedish and Norwegian with words meaning common people, mob, flock. The OED suggests this mow is ‘perhaps’ an early acquisition from Germanic languages and tentatively suggests a connection to post-classical Latin muga: mound, heap, and an isolated attestation of 1334 mugium haystack.

Another homograph mow , attested 1325 as a noun and later verbally, derives from Middle French mouwe ~moe; French moue and perhaps from ‘an unattested Frankish cognate of Middle Dutch mouwe: grimace. Following the pouting, scowling footprints of this word further back through the layers of time becomes more uncertain, although it’s possibly related to early modern Dutch mouwe muscle. This grimacing mow, now used verbally as in ‘to grimace and mock, to jest’, often collocates with ‘mock’ and ‘mow’ :

‘And now Yvonne Griffaton’s father, who had been implicated in the Dreyfus case, came to mock and mow at her.’ (1947,M. Lowry, Under the Volcano)

Breugel’s harvesters are not mocking; any grimaces may be the result of mowing in the mid-day sun. Their mowing involves wheat.

Wheat, a free base element has a small morphological family: wheat, wheaten, wheatish and various compounds: buckwheat, wheatgrass, wheatear, wheatmeal, wheat-sheaf, wheat-stubble.Wheat is more interesting than may appear from this modest family. There’s a whiteness to wheat which has been part of the English language for a long time. It’s attested around 825 in Old English as hwǽte, derived from Proto-Germanic *hwaitjaz :’that which is white’, most likely in reference to the grain. From here wheat can be traced back to a PIE root:*kweid-, *kweit- “to shine” . The shiny brightness present in wheat also underlies white, an etymological relative. And what about the harvesting of wheat?

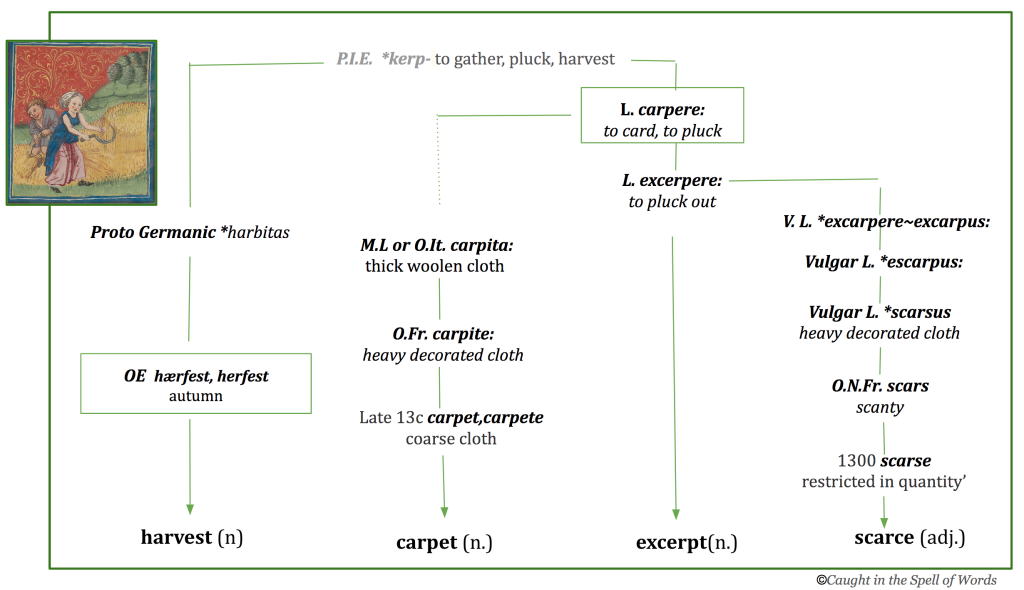

Harvest is the fruit of Germanic stock, Old English hærfest, hęrfest from Proto Germanic *harbitas from the ancestral root Proto Indo European *kerp- to gather, pluck and harvest. A surprising discovery was that carpet, whose etymon is Latin carpere ‘to card and pluck’, also derives from PIE *kerp. Unravelled, shredded and plucked fabric produced thick, woolen cloth known as carpita – in Old Italian or Medieval Latin. Carpet is attested in English via Old French around 1345, spelled variously as karpete, carpette, carpyte, carpit .This thick fabric functioned ‘ to cover tables, beds etc’ (OED) before it fell to the floor. Latin carpere is also the etymon of excerpt, <ex + cerpt > again suggesting plucking and extracting something from its source.

If harvest carries a connotation of ‘plenty’ and ‘plucked abundance’, it’s surprising to discover that scarce too shares the same etymon. It entered English around 1300 via Old French scars via Vulgar Latin and Latin excerpere to pluck out. Germanic harvest and its Latinate cousins all share an underlying denotation of gathering, plucking.

At the heart of Breugel’s painting is a sense of companionship. I smile at the company of monks in the distance who are in various stages of plunging into a pond and my eye returns once more to the harvesters resting in easy companionship beneath the tree – companions sharing food. With so much of the painting given to the the golden wheat crop, it’s apt that bread is the underlying denotation of companionship.

Etymologically, a companion, 1325, denotes a friendship formed around bread. An early sense of companion was one’s ‘messmate with whom one habitually eats meals’: <com + pane + ion>. The immediate etymon of companion is Anglo-Norman deriving from the ulterior etymon Latin panis: bread. This Latin etymon has produced pannier– initially a bread basket but extended to any large basket for provisions, and even to the frames, whalebone, used to expand a woman’s dress at the hips.There are also panniers, not baskets but waiters, who worked at the tables of the Inner Temple, one of the four inns of court providing legal training, selecting and regulating barristers within England and Wales. This sense of pannier has derived from pannierman from Latin. It’s interesting to note to note that pannier entered English in 1300 via Anglo Norman and had a variety of spellings none of which doubled the <n> until the 1500s.

Other related words are the compound pandemain, 1390, derived from Anglo-Norman pain demeine, pain demaine from AN pain bread + demeine ‘land held as one’s own’, after post-classical Latin panis dominicus. Pandemain referred to ‘white bread of the finest quality; a loaf or cake of this bread’ (OED)

Pantry originally ‘a room or set of rooms in a large household in which bread and other provisions are kept’ (OED). The panter or its variant form pantler was the officer in a household who supplied the bread and had charge of the pantry, the bread-bearer, even bread-controller regulated the distribution of bread in the royal household and had supreme authority over all the bakers of the kingdom; bread-choppers (1600) and bread-chippers (1616) pared the crusts – occupations long since faded.

Bread attested in 950, is of Old English origins, bréad, plural bréadru. The denotation then was “bit, crumb, morsel; bread”. Bread originally may have denoted a piece of food with its senses gradually shifting from ‘piece of bread’ to ‘broken bread’ to ‘bread’. The initial denotation of bread as ‘ piece, bit, fragment, was similar to Latin frustum’ (OED). However, beyond the Old English word, the breadcrumb trail is unclear. Some etymologists trace bread to a P.I.E. root *bhreu tentatively suggesting a link between bread and brew. Yet the O.E.D. states emphatically that there is no evidence for this. In Old English the word bréad is rare. So what was the usual word in Old English that referred to bread? None other than loaf – the close relationship indicated by the phrase a ‘loaf of bread’.

Loaf

OE hláf:loaf was the more common term for bread and like bread, attested from the 9th century. Some etymologists suggest a connection with Old English hlífian ‘to rise high, tower’, in reference to the ‘rising’ of leavened bread. The OE etymon can be traced to Proto-Germanic *khlaibuz , although beyond this the trail is uncertain. Whatever the the origins, before 1200 bread displaced hláf as the name of the substance, leaving loaf to carry the sense of the whole unsliced bread.

‘To loaf around‘ is not idling while snacking on bread. The homophone loaf, a verb, is the antonym of work, and a back formation of loafer as in ‘idler’. Loafer also denoted a type of shoe since 1939 (OED), presumably foot-ware for idle pursuits. This idling loaf, attested in 1837, is of uncertain etymology, but unrelated to the bready loaf .

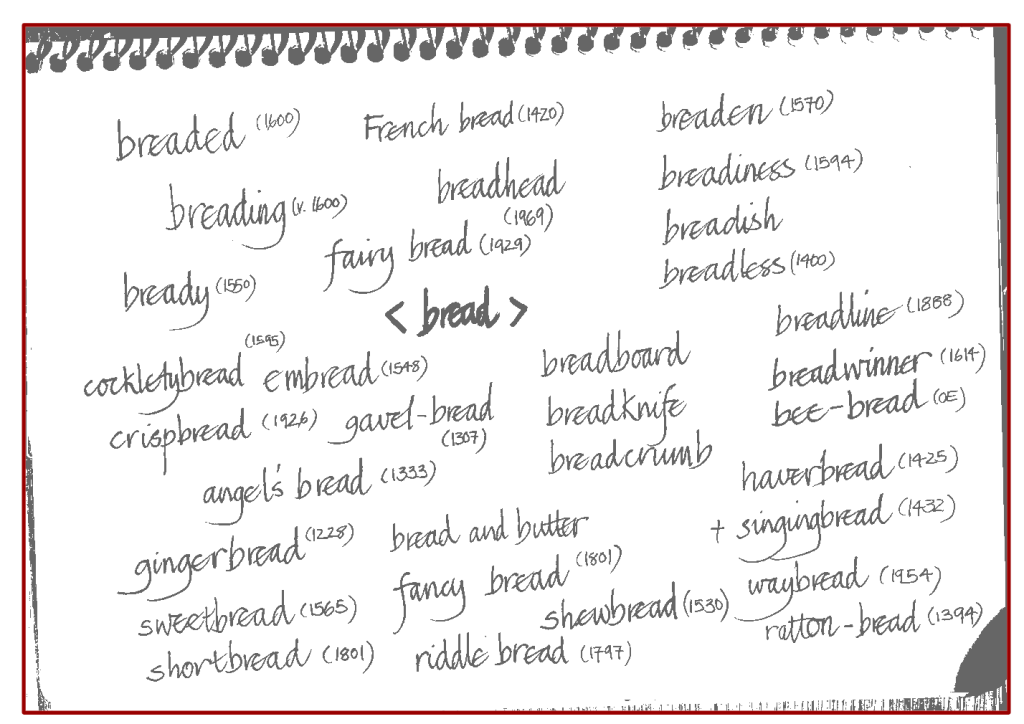

Notes above from my research into bread. All these words, harvested from the OED, have an intriguing back-story highlighting moments in time. Take gingerbread for example. Attested in 1228, I was surprised this had nothing bready about it- rather it was preserved ginger. It derived via Old French from Latin gingimbratus “gingered” from gingiber. It was folk etymology that adjusted the ‘brar’ , ‘brat’ to brede and thence bread. Waybread attested in 1954, is surprisingly recent. Inspired largely by J. R. R. Tolkien and adopted into fantasy fiction, it refers to ‘ a kind of sustaining food made for eating before or during a long journey, typically in the form of flat bread or wafers’ (OED).: ‘We [sc. the Elves] call it lembas or waybread, and it is more strengthening than any food made by Men.’ (J. R. R. Tolkien, Fellowship of Ring)

However, waybread a compound derived from the Germanic way + Germanic broad refers not to bread, but to the ‘broad-leaved plant of the way’ (the plant typically grows on well-trodden paths)(OED)

Lords, ladies and bread

The connection of nobility with bread may surprise us today, but possibly not to the bread munching harvesters in Breugel’s painting. They are duty bound to reap the harvest for an overlord. The Old English word for lord was hláford. This derives from an earlier OE compound hláfweard : hláf: bread and weard: guard which over time and with changing stress reduced to hlaford and so eventually to lord. A lord is the head of a household in his relation to the servants and dependents who ‘eat his bread’ , a sense comparable with OE hláf-ǽta : ‘bread-eater’, a servant (OED).

The original Old English form for lady was hlǣfdige a compound like hlafweard, that emphasizes the importance of bread.This OE word is composed of two elements hláf: loaf and an unattested OE etymon *dīge: kneader, or.”maid,” which is related to dæge “maker of dough.”

On the surface lord and lady appear as free base elements in present day English, yet contained within the words are the crumbled remains of bread and the power and control this wields; those who dispense bread, the staff of life, have power over the lives of others. Those who grow the grain to make bread, have lordship over harvesters.

And with this meandering through Breugel’s golden wheat fields and the words this inspires, I look at the mowing figures in the foreground and am reminded of the heat and sun and past harvests. Eleanor Parker in her brilliant blog A Clerk of Oxford notes the coinciding of autumn and the beginning of harvest celebrated with bread on Lammas day, OE hláfmæsse-dæg. ‘August 1 was Lammas, the ‘feast of bread’, the earliest festival of the wheat harvest when loaves made from the first corn were blessed. Six nights later comes autumn itself'(Parker,E.)

Below, an excerpt from the Old English Menologium, “month-set”— a book arranged by the months, where it tells of festivals marking the harvest and its plentiful abundance:

And þæs symle scriþ

ymb seofon niht þæs sumere gebrihted

Weodmonað on tun, welhwær bringeð

Agustus yrmenþeodum

hlafmæssan dæg. Swa þæs hærfest cymð

ymbe oðer swylc butan anre wanan,

wlitig, wæstmum hladen; wela byð geywed

fægere on foldan.

And [after the feast of St James] after seven nights

of summer’s brightness Weed-month slips

into the dwellings, everywhere August brings

to all peoples Lammas Day. So the harvest comes,

after that number of nights but one [i.e. on August 7],

bright, laden with fruits. Plenty is revealed,

beautiful upon the earth.