Tags

capricorn, carat, carrot, cerebral, cerebrum, cornado, cornemuse, cornicle, cornicopia, cornify, cranium, hart, horn, keratin, keratpid, migraine, reindeer, rhinoceros, rhinolalia, rhinologist, rhinorrhagia, rhinorrhoea, saveloy, unicorn

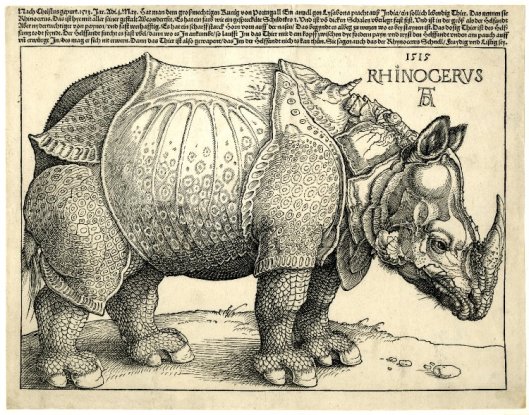

Sturdy, head down, nudging the confines of the frame, Albrecht Dürer’s 1515 Indian rhinoceros stands, armour plated and beady-eyed. Behind both artifacts—woodcut and the word rhinoceros, there is a story.

Of course we analyzed ‘rhinoceros’. However, before the immediate rush to resources, I ask students to hypothesize and justify their thinking. This is as much of an assessment as any formal ‘test.’ Slowing down to consider and reconsider, to justify a hypothesis reveals understanding and misconceptions. It also means that students read the resources with greater care to confirm or revise their initial hypothesis when examining the Online Etymology Dictionary, rather than approaching this resource with a mindless expectation that the answer will reveal itself in a neat morphological algorithm.

You will see from the video above that these students recognized ‘-os’ was a Greek suffix and speculated that the digraph ‘rh’ is too of Greek origins using evidence to support this claim. This group of students finally concluded that ‘rhine+o+cere+os’ made structural sense. ‘rhine’ is a bound base element, ‘o’ a connecting vowel letter that students now spot regularly and ‘cere’ another bound base element- not as they had initially thought another suffix . Students hastily assumed that when a base has been identified anything that follows will be a suffix!

Note how the students now automatically insert a potential final, non-syllabic ‘e’ in the final position of both bases. We have as yet no evidence of this ‘e’ surfacing in other words sharing these bases, but its insertion prevents the possibility that the final consonant in both bases will double with the addition of a vowel suffix. Some students are able to justify its inclusion, for others its a pattern they have observed that will emerge more clearly as their understanding grows.

The OED finds the earliest written use of rhinoceros was in 1398 entering English via Anglo-Norman and Middle French rinoceros. While in Middle French it was recorded variously : rynoceron (15th cent.), rhinoceros, rhinoceront, their etymons from classical Latin rhīnocerōt-, rhīnocerōs, also rīnocerōs, and in ‘post-classical Latin and scientific Latin also rhinoceront- , rhinoceron’. However, these were derived from the Greek ῥινοκερωτ- , ῥινόκερως. So ῥινο- ‘rhino- ‘ compounded with ancient Greek κέρας: keras horn. pιν :rhin is used before a vowel which derives from ῥις: rhis: nose. Beyond that, little more is known.

The first base element of the connected compound ‘rhinoceros’ is ‘rhine’ and found in a host of words including these intriguing words: rhinencephalic: the olfactory lobe of the brain; rhinolalia—nasal speech; rhinologist—a nose specialist; rhinorrhagia—excessive nose bleeding and excessive mucus discharge is indicated in rhinorrhoea. We enjoyed discovering the specific name for the hairless moist area at the tip of the nose in many mammals as rhinarium, it’s also the term for the ‘flattened olfactory organ situated on an antenna of insects’.

Our analysis of the elements ‘rrhoea’ and ‘rrhage’ was based on evidence from the OED which states that ‘Classical Latin –rrhagia is derived from ancient Greek –ραγία : rhagia to denote ‘bursting, breaking forth from’. ῥαγ- rhag is the stem of ῥηγνύναι :rhegnynai: to break, burst (of uncertain origin).’ We noticed when initial in a base element, /r/ is represented by the digraph ‘rh’ and after a vowel letter /r/ is ‘rrh’.

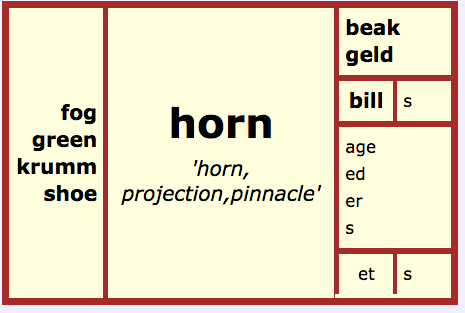

The creation of matrices are so instructive—they force us to question elements,suffixing patterns, suffixes, connecting vowel letters, but ultimately it’s about meaning. It’s the placing of of all the close relations, those sharing a base element and therefore root, in the matrix. Matrices represent synchrony —they artfully reveal the morphemic elements of words sharing a common base element that currently exist in the language.When examining or constructing the matrix all elements are arranged and on view so that we can contemplate and synthesize them. For this reason a matrix is so much more powerful than a list which is finite and never exposes the elements. In constructing all the matrices of this post, we have ruminated long and hard about many of the elements such as Greek ‘-ῖτις’ ‘itis’ which ‘was already in Greek used to qualify νόσος :nosos:disease, expressed as ἀρθρῖτις : arthritis—disease of the joints. Apparently on the analogy of the diseases: νεϕρῖτις : nephritis—disease of the kidneys, πλευρῖτις : – pleurisy, ῥαχῖτις: rhachitis,’—spinal disease, –itis’ generalized in modern medical Latin and become in English the term for inflammation. It is even now used as a word- a base element itself.(OED)

The second bound base element, ‘cere’ in rhinoceros: ‘rhine+o+cere+os’ is from Ancient Greek κέρας , κερατ- : horn. The letter ‘k’ was ‘little used in classical Latin, conforming most of its words to a spelling using ‘c’. This pronunciation of ‘c’ shifted to /s/’ (Online Etymology Dictionary). Students saw that Greek κέρας , κερατ- : horn derived from the reconstructed PIE *ker-(1) horn or head.

This family is old and has been remarkably fertile—the idea of ‘horn’ and ‘head’ thrusts into all branches of the Indo-European language family. Ancestors from the Greek , Latin, Old English and even Sanskrit branches have impacted many offspring in English to name horned animals, horn-shaped objects, and projecting parts.

The Greek relatives:

The Greek branch of the family :κέρας: keras ~ κερατ: kerat: leads to English keratin:‘a fibrous protein forming the main structural constituent of hair, feathers, hoofs, claws, horns.’ Derivatives are scientific referring to the horny texture of the cells of the epidermis or ‘coating of pills with a horny substance, so that they may pass through the stomach without being dissolved’ keratinization, keratinize. In mathematics a keratoid is a horn shape and a keratectomy is the removal of part of the cornea to correct myopia. However, the most surprising of family members is carat—the measure to determine the purity of gold.

Of carat and carrots- homophones from the same root

The connection between carat and Greek κέρας:keras was a surprise. Spelled variously from the time of its attestation in English (1552), its immediate etymon was French carat, and that was via Italian carato which was from Arabic qīrāṭ (and qirrāṭ ) ‘weight of 4 grains’, and ‘according to Freytag from Greek κεράτιον ‘little horn, fruit of carob or locust tree, a weight = 1/ 3 of an obol’. (OED) The humble carob bean, horn shaped, had a reputation for uniformity in weight. From the 1570s carobs were used for measuring the weight of diamonds. The Greek measure was equivalent to the ‘Roman siliqua, which was one twenty- fourth of a golden solidus of Constantine; hence the word took on a sense of “a proportion of one twenty-fourth” and so 18 carat gold means 18 parts gold to 6 parts alloy.’ (Online Etymology Dictionary)

Carat and carrot are homophones and also surprisingly etymologically related. The vegetable carrot was familiar to Greeks and through them the name Greek καρωτόν karoton “carrot”. The Romans too knew of carrots, Latin carōta, and they introduced them to Britain. However, as Ayto states in his entertaining The Diner’s Dictionary, we would be hard pressed to recognize ‘this dingy, yellowish tough root as a carrot today’.

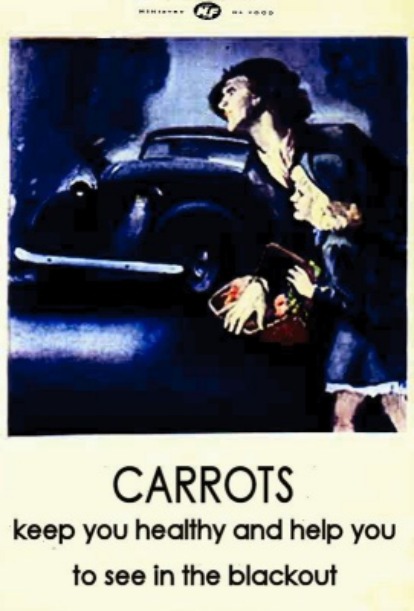

Rather, the modern orange carrot emerged from Afghanistan initially as a purple rooted variety, then spread its roots westward conveyed by Arabs. Spreading from Spain to northern Europe and finally in the Middle Ages to the ‘Low Countries’, the orange carrot of today was cultivated. It was in the sixteenth century that it finally crossed the English channel to appear in Britain along with its French name carrotte. It became rooted both in British soil and its colour in the popular imagination, so that expressions such as carroty and carrot-head were common epithets for the red-haired by the seventeenth century. By world war two the carrot was common enough in England and readily available compared to other food sources, so that the propaganda of carrots stimulating excellent eyesight and night vision was born. And it’s link with horns and therefore rhinoceros? The Greek καρωτόν karoton ” evolved from κάρᾱ kara “head, top” and this, Online Etymology Dictionary suggests cautiously, is perhaps from PIE *kre-, from the root *ker- (1) “horn, head”.

While sugar was rationed during World war 2, the humble carrot was not and propaganda concerning its powers to develop night vision during blackouts became rooted in the popular imagination!

AS with carat and carrot, cranium too has been Latinized but is also from the Greek branch of the family, Greek κρᾱνίον skull. It was adopted into Medieval Latin and first written evidence in English is from 1543. Less obvious is the etymological connection to migraine. Migraine entered English via Middle French in 1425 from French ‘migraine’ where it developed from Old French with a sense of ‘pique, vexation’. The ‘mi’ may be all that remains of Latin ‘hemi-‘ which combined with ‘crania’ leads to hemicrania ultimately from Greek ἡμι-hemi- and κρᾱνίον: kranion: skull.

The Latin relatives: ‘corn’, ‘cerebr’

There are even more wordy delights down the Latin branch of this ancient family . Find as many as you can from the matrix below centered around the free base element ‘corn’. In all words in this morphological family, the horn projects.

English ‘corn’ as in the hardened skin of foot or hand derived from Old French corne which in the 13th century referred to animal horns and later toughened skin. The Old French etymon derived from Latin cornu: horn and ultimately also from PIE *ker-(1).

Did you know that a horn wound was a cornada? A matador’s nightmare! Or that cornucopia, a compound formed first as a phrase in Latin, refers to the horns of the Greek goat Amalthea who nursed young Zeus? The second element of cornucopia, bound base element ‘cope’ is formed from Latin com +ops and denotes power, resources. This is the same source as Latin opus work. The myth tells of Amalthea‘s horn breaking but in various versions the horn is blessed and becomes a symbol of abundance. Cornet can refer to either the wind instrument originally made from horn or a headdress particularly that of the sisters of Mercy or one where the lappets of lace hang down the cheeks.

Cornicle—‘little horn’ refers to the horns of a snail. The ‘-icle’ appears to be a suffix as evidenced by cubicle, testicle, particle and follicle. While the horns of the snail may seem diminutive, not so for a marginalia knight of medieval manuscripts. Theses knights cower and tremble at the alarming cornicles! Read more about this here on The British Library blog: Knight vs Snail .

The underlying metaphor of corner is that of a projecting point. Corner is attested around 1278 from Anglo Norman and derived from Vulgar Latin cornarium which is derived from cornu: horn. The unusual cornery is an adjective of 1576, a lurking word, ‘abounding in shadows’. Cornage is horngeld or a form of feudal payment determined by the number of horned cattle and a cornemuse of 1384 ,’corn+e+muse’ is a connected compound and an early form of the bagpipe. To cornify is to cuckold—and yes cuckold is etymologically linked with the cuckoo. (Read about cornify and horns and the word cuckold).

Even the English county Cornwall is etymologically related. Old English Cornweallas , ‘Corn Welsh’ from Welsh Cernyw, Cornwall is from proto-Celtic *Cornovjo-s, *Cornovja. The OED cautiously states it Cornwall is probably derived from Celtic corn, cornu, ‘horn’, in sense of a projecting corner or headland. (OED) The Online Etymology Dictionary states Cornwall has a literal sense of “peninsula people, the people of the horn”.

Cerebral 1816, “pertaining to the brain,” from French cérébral (16c.), from Latin cerebrum “the brain” and “the understanding” is from PIE *keres-, and too from the PIE root *ker- (1) “top of the head”. The sense of “intellectual, clever” is comparatively recent, from 1929.

Latin cerebellum, is the diminutive of cerebrum brain; in ancient Latin it was used only in sense ‘small brain’. For this sense the Romanic languages have formed a secondary diminutive French cervelet, Italian cervelletto. (OED)

To consider the morphological structure of both cerebral and rhinoceros is an opportunity to also examine the graphemes of the base and to investigate the phonology of ‘c’. Why in cerebral and and rhinoceros is the ‘c’ pronounced /s/? When does the grapheme ‘c’ become pronounced as /k/?

Of Saveloys and Rhinoceros

Saveloy is a free base element but has derived from the same root as cerebral and cerebellum. The 19th century saw saveloys rise to sausagey prominence – Dickens refers to them in Pickwick Papers and in the musical version of Oliver, orphaned children sing wistfully of ‘pease porridge and saveloys‘. Saveloy, attested in 1784 and etymologically a’ brain sausage’, is the Anglicised version of French ‘cervelat ‘ which was borrowed from Italian cervellatta, a diminuitive of cervello brains which derived from Latin cerebellum and this takes back down the path to PIE *keres– from *ker-(1) and so a distant relative of the second element in rhinoceros.

The Germanic relations: ‘reindeer’, ‘hart’ and ‘horn’

Old English ‘horn’ has led to the present day free base element ‘horn‘ which refers to the projections from the head of animals as well “wind instrument” originally one made from animal horns. This too traces back down the Germanic family branch to the reconstructed Proto-Germanic *hurnaz and finally to the PIE root *ker-(1 ) Derivatives from these roots have led to the related base elements : bound ‘rein’ from ‘reindeer‘ , and the free base element ‘hart’ from Old English heorot which also lurks in the shadows of the name Hertfordshire—literally a ford frequented by harts!

Above harts 1520, “Harts. A bone, a feather, animal scratching itself. A bird.” From an herbal and bestiary , The Tudor Pattern Book, published in East Anglia c.1520-30 via Bodleian MS. Ashmole 1504. Note the horns.

An Aside: Pattern books

Medieval book illustrators aimed to produce rich illustrations and kept ‘pattern books’ as notebooks to record designs, figures, motifs, borders that caught their fancy. These were all derived from earlier works such as stained glass windows, books, paintings. Such notebooks “helped to circulate artistic traditions and ideas around the manuscript making community. Because they were working documents, passing between many different people, few medieval pattern books have survived.” Pattern books are part-bestiary, part-herbal and an important visual record of early cultivated plants. This pattern book was produced in East Anglia in about 1520.’ BibliOdyssey

Dürer’s Rhinceros

There have been two famous captives on the small island of St Helenea, McGregor reminds us—Napolean of course, and briefly one that attracted gasps of admiration and wonder, an Indian rhinoceros en route to Portugal!

The rhinoceros was a gift from from Sultan Muzafar II, ruler of Gujarat, to the governor of the Portuguese colony in India. Somewhat overwhelmed by the animal, the governor forwarded this wonder to King Manuel I of Portugal. As Neil Macgregor observed “getting a rhino weighing between one and a half tons onto a 16th century ship must have been quite a task” (MacGregor, A History of The World in a 100 Objects p.483)

The rhinoceros and keeper Osem left India in January, 1515 with ‘vast quantities of rice—an odd choice of diet for a rhino but less bulky than his usual fodder’. 20 May, 120 days after departing India, the rhinoceros arrived in Lisbon.

The bewildered beast was for the gaping Europeans another recovered antiquity—Pliny the Elder had had described such creatures in Natural Histories. For Europeans these creatures, once star attractions in Roman amphitheatres, were now known only through Pliny’s text. The Europeans were astonished and the rhinoceros doubtless bewildered.

The Portuguese king had elephants in his menagerie and to test Pliny’s claim that the elephant and rhinoceros were bitter enemies, he organized an encounter. However, while the rhinoceros advanced towards the tall beast, the elephant, overwhelmed by the crowds, fled.

Rhinocerus fever gripped the Europeans: sketches were made, an Italian ‘ditty’ composed in homage and letters written describing the wondrous creature. It was one such sketch and a letter that made its way to Nuremberg inspiring Dürer’s woodcut. His wood cut led to an estimated 4000 to 5000 copies of this print sold in Dürer’s lifetime. Yet Dürer himself never saw a live rhinoceros.

Looking to curry favour and approval with the Pope for Portugal’s empire building, the King sent the rhinoceros as a gift to the pope. However, the ship carrying the rhino sank in a storm off La Speza and the unfortunate rhinoceros, chained on the deck, for a brief moment the wonder of Europe, drowned.

Tragedy still continues to haunt the rhinoceros today, but this time it’s the Sumatran rhinoceros, the smallest of the species. We learned in a seminar through visiting documentary producer Lydia Lubon, an alumnus of our school, that the Sumatran rhino is rapidly ‘running out of space and time’. As we watched the documentary we realized we were staring extinction in the face.

The collective term for a group of rhinoceros is a ‘crash’ and once the earth resounded with rhinoceros crashings—today it’s more of a murmur, faint and pain-tinged. Rhinos are wanted animals, slaughtered for their horns. ‘… for the most part solitary animals but in large groups they are a crash, a term that is surprisingly in the ancient books of venery. While crash speaks to the rhino’s charge, much of the rest of the animal’s life is subsumed with delicacy. Female rhinos communicate with their young with a series of gentle, high pitched mewls and attract mates by whistling softly through their noses.’ ( A Compendium of Collective Nouns, 172)

By a focus on just one word ‘rhinoceros’, we have uncovered many words. We can so easily be ensnared in Listomania, duped into thinking more words are always better and require students to look up the definition, use in a sentence and then move on to the next in the endless list to plug their vocabulary deficits. Yet think about rhinoceros and consider how many other words on our quest we have encountered, how deeply we know this word.

Word investigations illuminate all subjects showing that words, events and cultures coalesce and when understanding the word and its relatives, we understand more than the word. Through one word, the world, the past, present and future is opened to us. Here in this nose and horn filled quest, we have touched on history, learned of a time when the Greeks and Romans knew and encountered this wondrous creature, encountered art and science and in bringing these fragments together we can only wonder at the folly of mankind and the rapidity with which we destroy the world and the creatures around us.

’50 million years ago many diverse rhino species were found in North America, Europe, Africa and Asia … 350-8 million years ago, the furry Wooly rhinoceros, close relative of the Sumatran rhinoceros roams Northern Europe and East Asia. Human hunters may have caused the animal’s extinction.’ Between 1600-to 1900 the population of the Indian rhinoceros which once roamed in great numbers through the Indus, Ganges and Brahmaputra river basins of India Pakistan and Nepal is decimated. In 1910 less than 50 of the animals were found in India.

Africa’s s northern rhinoceros has been ‘driven past the point of no return. There are only five left alive, and only one male. He is under constant armed guard to protect him from poachers, and has even had his horn removed to deter them. The other African species, the black rhinoceros, is critically endangered. There are thought to be seven or eight subspecies, of which three are already extinct and another is nearly gone’. (BBC,Baraniuk)

The smallest of the species, the Sumatran rhino, is too critically endangered represented by a mere three captive individuals. it shares with the Javan rhinoceros ‘the bleak distinction of being world’s most endangered rhino. ‘(National Geographic)

The Bornean rhino in Sabah was confirmed as extinct in the wild in April 2015, with only 3 individuals left in captivity.

The mainland Sumatran rhino in Malaysia was confirmed to be extinct in the wild in August 2015.

‘In March 2016 there was a rare sighting of a Sumatran Rhino in Kalimantan, the Indonesian part of Borneo. The last time there was a Sumatran Rhino in the Kalimantan area was approximately 40 years ago. This optimism was met with despair as that very specific Sumatran Rhino was found dead several weeks later after the sighting. The reason of the death is currently unknown’. (CNN News, April 2016)

Once there were creatures with noses and horns, they roamed Europe, an artist Dürer in the 16th century was so inspired and drew one. Today we watch the rhinoceros hurtle towards extinction.

Read more about the Rhinoceros below:

BBC The Story of Rhinos and how they once conquered the world:

Rare Sumatran Rhino Found for the First Time in 40 years

Live Science Facts about Rhinos

One Kind:Sumatran Rhinoceros and video

No one illustrates better than you, Ann, how the study of a word is profoundly intertwined with the study of Everything else.

LikeLike

Thankyou for reading this post Gail. I love how orthography IS the key to Everything!! I have learned so much from the one word!

LikeLike

Ann and students, I just can’t ever get enough of the winding way you explore words–and the joyful eloquence of your writing! This post resonated with me for so many reasons! In our recent exploration of Greek base elements, students were working from a list (in the original Toolbox) that gave “cerate” as the base for “horn”. One of our team could see that this didn’t fit with the structure of “rhinoceros” and hypothesised “cere”. I was delighted to see how naturally he challenged the accuracy of a resource.

During our exploration, which had sprung from a poem called “Pachycephalosaurus” by the fittingly-named Richard Armour I threw out the word “pachyderm” thinking they’d know it. None did. Turns out it describes not just elephants, as I had thought, but any of a general group of “thick skinned” animals, including the noble rhinoceros. This archaic classification struck me as both wonderfully exclusive and sweetly subjective as opposed to, I postulated, “ungulates”, of which the rhino is also a member. But when I went–as I encourage you to do–to the Wikipedia reference on ungulates, it turns out this is also falling out of taxonomical favour. Here I found a dizzying spiral of sub-sub-sub classifications and astonishing orthographic concoctions as taxonomists work to separate these creatures into tidy categories. I was struck by the similarity to orthography: like animals, the more we know of words and their sometimes-hidden structures and histories the harder it is to separate them into unrelated groups.

I first saw the rhino illustration at the head of this post as a child because here in Canada we had for many years a satirical political party, The Rhinoceros Party, which used this image as its logo. Their reasoning: the rhinoceros was an appropriate symbol for a political party since politicians, by nature, are “thick-skinned, slow-moving, dim-witted, can move fast as hell when in danger, and have large, hairy horns growing out of the middle of their faces.” Bit harsh, but this was the party that promised to repeal the law of gravity and “promote higher education by building taller schools” so weigh their opinions in that light.

Finally, thank you for drawing attention to the plight of this creature. I will almost certainly never see a rhinoceros in the wild (how long will anyone?) but did have a fairly close encounter with one at a zoo some years ago. I found myself weeping at the sight of this docile survivor. Not quite thick-skinned enough, either of us.

LikeLike

Skot thank-you for reading the post and for this wonderful response. I was not aware of the wonderfully named Richard Armour and his poetry. I found and loved Pacycephalsoaurus then spent some time just reading about Armour himself and his prolific writing. I love what he said here:

“I am fascinated by words.Perhaps,” he continued in an interview in the anthology “Contemporary Authors,” “because I took a Ph.D. in English philology at Harvard, studying 10 dead or deadly languages. Dictionaries surround me while I write and I call my place of work my wordshop. I envy Wordsworth his name, the perfect name for a writer. . . .”

As for the taxonomies of animals ( and plants) well what a feast there for lovers of words. I’m fascinated by the desire to name and label and classify and love pouring over tree diagrams of animal and plant life.

LikeLike

I also note that a horn is called (קֶרֶן) (keren) in the Hebrew Bible.

LikeLike