This 1944 map shows the flux of the Mississippi River for the past 1000 years, each colour showing an old channel.The history of its change was recorded in the Geological Investigation of the Alluvial Valley of the Lower Mississippi River, published by the Army Corp of Engineers in 1944. Rivers feature in this word investigation and this map echoes the flux occurring in words, the twists and turns of meaning as the past, like the meanders above, impacts the present.

Word investigations are rarely carried out in our humanities classes just for the sake of developing skills to investigate a word, or to teach spelling or to expand a student’s vocabulary. Of course, the investigations do all this, but the primary aim of any investigation is to deepen understandings of the concepts, texts and issues at the heart of our year long conversations in humanities.

Most often our orthographic investigations arise from a picture book which helps frame our discussion, serves as an introductory exploration of themes, and is a text that we can return to, only to discover with each return that it is not a going back or a repetition of the initial experience, but that with each rereading we discover and understand more. We read these texts and images conversing about motif, theme, character development, and note the balance between word and image, the dance of the visual in harmony with the word.

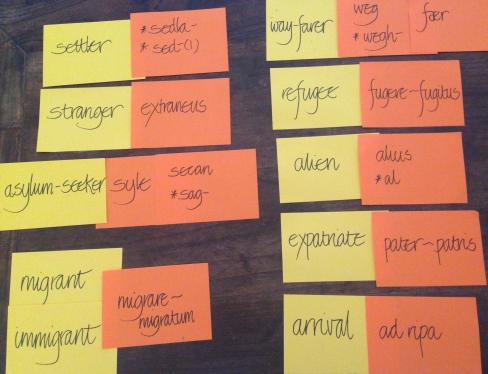

Shaun Tan’s The Arrival is one text students continue to pour over. We spent a week reading and discussing this rich narrative. This was a surprise to students as there were no words – at least no English words, any text within the book being written in the language of the Nameless Land. We discussed the way a settled group perceive newcomers, the arrivals. We wondered how the names we attach and labels we give for the arrivals effect our outlook and their fates. These words became the basis of our word study.

Ranking

As we discussed the various words for people who move or shift places, I asked the class to rank them on a continuum from positive to negative. Any time words are compared involves discussing what it is and what it is not. Synonyms are not identical. Similarities in meaning exist but each is not a replica of the other. They fall along degrees of proximity to a particular word. Two identical words cease to coexist in English, one will shift and change to take on slightly different connotations, such as occurred with Old English derived ‘heaven’ and the arrival into English of Norse ‘sky’. I did not specifically ask students to discuss the meaning, but the thinking necessary to rank, demands clarity about each word. Listen to the excited group discussions, then whole class discussion.

Matching the denotation

Students matched the denotations I had printed from the dictionary, carefully reading these arguing, questioning, and discussing words.

Matching the root to the word

Next I gave each group the roots only – no root denotation, no indication of the language of origin. I overheard statements such as, “Isn’t <ere>‘Latin?” “Why the asterisk?” “Why is there a hyphen after some roots? ” “There’s a<y> , does that mean it’s Greek?” Examining the root, can help students to identify the base element and graphemes that surface in present day English.

The discussion around connotations, hypotheses as to the elements, matching word to denotation, and matching word to root, raises questions to pursue in research and prepares the students for a thoughtful interrogation of the resources – The Online Etymology Dictionary, John Ayto’s Word Origins and the OED. Their hypotheses and questions provoke the impetus for the next stage of the investigation. Each group or pair of students chose a word to investigate further. Below samples from the research of ‘refugee’ and ‘migrant’, both words students had considered when reading the The Arrival.

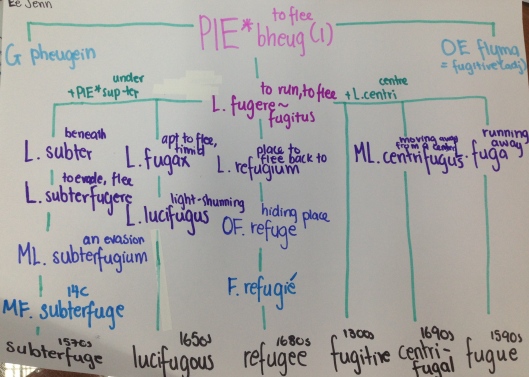

Student research on refugee

The students below researched ‘refugee’ tracking its route from 5,500 years ago into present day English. They discovered that it arrived in English in the 1680s. Refugee <re+fuge+ee> is derived from the Latin infinitive ‘fugere’ and the past participle ‘fugitivus’, denoting fleeing, taking flight. Buried in the word refugee lurk suggestions of persecution and massacre. Discovering the date of the attestation of this word in English, we wondered: what event or forces propelled this word into the English lexicon at that particular time?

The bloody persecutions behind refugee:

Investigation of the period refugee entered English, uncovered power struggles, religious persecution, bloody massacres, revoking of edicts, and calculated terror. St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre of August 24, 1572 was fuelled by hatred towards Huguenots and the fear of power slipping from Catholic hands. This provoked the bloody Catholic rampage where the streets of Paris were littered with Huguenot bodies.

Painting of the St Bartholomew Day Massacre by Huguenot painter Francois Dubois. Note the body of murdered leader de Coligny hanging from the window. Note also the same leader’s body shown decapitated on the ground under the window with Duc de Guise standing behind it. Note also the picture of much vilified Catherine de’ Medici emerging from the Louvre to inspect the bodies.

The spark igniting this orgy of violence was the wedding of Huguenot Henri de Bourbon, King of Navarre, to Catholic Marguerite de Valois, daughter of Henry II and Catherine de Medici, and sister of Charles IX. Many prominent Huguenots had gathered in Catholic dominated Paris to attend the wedding, a dynastic alliance ‘intended to cement the peace between Catholic and Protestant factions in France after a decade of civil and religious war. It failed miserably.’ (B. Diefendorf).

Poor harvests and increased taxes resulting in increasing food prices juxtaposed with the luxury of a royal wedding fanned tensions among an already hostile population. Two days earlier there had been a bungled assassination attempt of Admiral Gaspard de Coligny, the military and political leader of the Huguenots. With orders to cull Huguenot leaders, including Coligny, the bloody flames of slaughter and hatred spread throughout Paris and the countryside. When a group, led by the powerful Catholic Guise, dragged Coligny from his bed, killed him, and threw his body out of the window, the tension exploded in a wave of popular violence.

Protestants were hunted throughout the city, including women and children. Chains blocked streets to prevent escape from the mob.The bodies of the dead were collected in carts and dumped into the Seine.‘Corpses floating down the Rhone from Lyons are said to have put the people of Arles from drinking the water for three months'(St. Bartholomew’s Day). Modern estimates for the number of dead across France vary, from 5,000 to 30,000. (Mikaberidze, Atrocities, Massacres, and War Crimes)

Not surprisingly shortly after this event in 1578, the word massacre is attested in English with the OED citing Scottish historian of the time, Robert Lindsay of Pitscottie: “ The xxiiij day of August..the grytt..murther and messecar of Paris wes committit.” Massacre “wholesale slaughter, carnage,” from Old French macacre, macecle “slaughterhouse, butchery,” of unknown origin; perhaps related to Latin macellum “provisions store, butcher shop’ (Online Etymology Dictionary). The OED refers to theories linking the word to mace– the ‘weapon consisting of a heavy staff or club, either entirely of metal or having a metal head, and often spiked’.

The 1598 Edict of Nantes ended the French Wars of religion by granting the Huguenots religious freedom. However, this was a fragile tolerance as Henry IV’s successors wanting an ‘absolute monarchy , continued to feel threatened by the Hugeunot power and a new wave of persecution began’ (Flavell). With a Huguenot revolt of 1629, Cardinal de Richelieu declared void the political clauses of 1598. In 1685 Louis the XIV revoked the Edict of Nantes causing an escalation of vicious persecution.

50,000 French Protestants fled to England with 10,000 fleeing to Ireland, all part of a mass exodus of 200,000 people. 750,000 Huguenots endured in France under oppressive “dragonnades”, the domestic terror whereby soldiers with’ a licence to bully, plunder and abuse were forcibly billeted on Protestant homes'(Independent).

Refugee in English dates from the exodus of French Huguenots who migrated after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes. Diarist John Evelyn wrote of this in 1687 : “The poore & religious Refugieès who escaped out of France in the cruel persecution.’ Refugee initially denoted “one seeking asylum”changing after 1914 to one fleeing home and in this sense to civilians in Flanders heading west to escape fighting in World War I’ ( Online Etymology Dictionary).

These refugees were not always embraced in England. As early as 1631, the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers claimed its members were “exceedingly oppressed by the intrusion of French clockmakers”. In 1708 a “Foreign Protestants Naturalisation Act” offered most Huguenots citizenship rather than “denizen” status. Yet the Church of England was suspicious of Calvinist worship and, ‘at least until the 1690s, pressed hard for French conformity to Anglican rites.'(Boyd Tonkin: Independent:Refugee Week). Of those fleeing to England, many Hugeunot settled in Spitalfields area of London where food and housing were cheaper and more freedom from ‘the economic control of the guilds.’ Spitalfields had a silk industry but with the influx of skills and Huguenot diligence, the industry thrived and was regarded as ‘weaver town’.’The wealthier Huguenots built large houses in Spitalfields, both for their families and for the weavers they employed. These houses, which still remain, are distinctive, with enlarged windows in the attic to let in the maximum light for the weavers.'(BBC) Gradually these arrivals integrated and in doing so even their names became Anglicised, such as LeBlancs to White,the Tonneliers, Coopers.The French refugees took on the occupations not only of weaving, but gold- and silversmithing, clockmaking, furniture making, printing and bookbinding, papermaking. Huguenots also made important contributions to the fields of science and medicine, politics, law and the military.

One student’s research on the word refugee and some of the family.

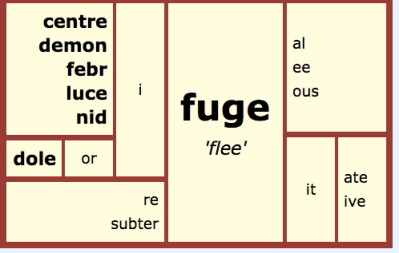

While our investigation focused on refugee, we enjoyed the discovery of compound words such as lucifuguous, shunning the light, nidifugous fleeing the nest, and demonifuge referring to ‘a substance or medicine used to exorcize a demon; (also more generally) anything thought to give protection against evil spirits'(OED).The latter is attested in 1754 with examples cited in the OED of incense, priests’ robes, peals from church bell towers and salt as possible demonifuges. Not a word of regular conversation or idle banter these days.

All year we engage in conversations and readings about identity. We talk about the forces shaping us, how others perceive us, the image we present to others and how we are perceived by others. It becomes a weaving in and out of history, the perils of labelling others and of courage during times of oppression – it’s a year long conversation around difference and belonging.

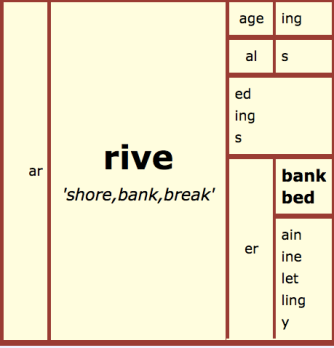

Before we investigated the morphology and etymology of ‘arrival’ students considered what it is ‘to arrive’. Talking first in pairs, then small groups and finally as a whole class we shared what we understood about ‘arriving’.

Implicit in ‘arrival’ is a ‘departure’ and an ‘elsewhere’. To arrive means you must have been somewhere else. ‘Arrival’ suggests an end point has been reached, a destination, a separation from the other. Listen carefully – can you hear the faint rustlings from over five thousand years ago echoing in the present, the faint tearing and scratchings, perhaps the soft splash of oars in water?

We followed the route, the journey of ‘arrival’ through Anglo-Norman French, via Old French to the Latin phrase ad ripa ‘ to shore’. Arrive is attested in 1275 in English as a verb and about 100 years later it is used nominally. Once we discovered the Latin root, we were able to trace the etymological trails to a Proto-Indo European ancestor and the routes of other relations migrating to English, other ‘arrivals’. In our scratching through the layers of time we uncovered family we would never considered as relatives: the Germanic ‘rift’, ‘riven’, ‘rivet’, ‘rifle’ and the Latinate ‘riparian’ and ‘river’ as well as the borrowed words, also Latinate, flaunting their ‘foreignness’ as loan words in English today – French riveria and Spanish ria.

Rifle: The verb rifle as in plundering, looting, or carrying off booty is of Germanic origin as is the weapon rifle. Both share the same Germanic and ultimately PIE root *rei- : scratch, tear, cut, but entered French en route to English. Plundering, booty-hauling rifle is the earlier arrival, attested by the OED in 1391 as an Anglo-Norman word. A rifle, the firearm, is attested in 1775 from the US as a ‘type of gun, usually fired from shoulder level, having a long barrel with a spirally grooved bore, intended to make a bullet spin and thereby have greater accuracy over a long distance. Also: an artillery piece having a spirally grooved bore’ (OED) . The compound ‘rifle gun’ was earlier in use from 1685.

Reap: is ‘probably ultimately from the same Indo-European base as rive ‘although the exact relationship is difficult to explain phonologically,’ (OED). Ayto suggests tentatively that reap may well go back to PIE root*rei- to to tear, scratch and ‘hence denote the ‘stripping of fruits and seeds from plants’. Ripe is from Old English reopan and according to the OED of the same Germanic base as reap and therefore rive, probably with original sense ‘that which is (ready to be) reaped or harvested’.

Not fooled by superficial similarity

It’s tempting to connect derive and rival to arrive, but really you would be paddling up the wrong stream! Derive, rivulet and even rival are connected morphologically – they share the same base element and on the surface this appears similar to arrive, but investigate further, to the root structure to see that these have evolved from Latin rivus “stream, brook,” from PIE *reiwos, from root *reie- “to flow, run” ( Online Etymology Dictionary).

Derive, rivulet, and rival are flowing, watery words. When something is derived from something else, it is a flowing away from. A rivulet is a diminutive form of Latin ‘rivo’ from Latin rivus stream or brook. As for the watery flow in rivalry, a rival we discovered, is one who is paddling in or sharing the same brook – it’s easy to see how this developed from neighbourliness to a sharp competitive edge : ‘Its etymon, classical Latin rīvālis (originally) person living on the opposite bank of a stream from another, person who is in pursuit of the same object as another from rīvus stream'(OED).

River on the other hand is is about tearing and scratching and cutting, the process of river formation. River initially referred to the banks, rather than the flow of water although the Old French riviere extended to include the flow of water and it was the dual senses of river, both banks and water, that Middle English adopted in its ‘borrowing’ of ‘river ‘in the latter half of the thirteenth century. Yet for such a common feature of the landscape, river is somewhat of a newcomer. Before river flowed through English, ea was the common word for flowing water, rivers. It is attested around 896, and according to the OED is still used in Lancashire, the fen country, referring to drainage canals. Ea‘s distant Latin relative is aqua.

Matrix:

In forming a matrix, it’s always tempting to add as much as possible. But to what purpose? A matrix is a gathering and an appreciation of the elements that constitute an immediate family in present day English. It offers the reader a chance to slow down and consider. A matrix, like all good portraits, should not be cluttered. This is a morphological portrait of a family and as such reflects the immediate relationships around a single base element in present day English. A matrix is strictly synchronic and so only the Latinate branch of the family is included in this matrix despite the temptation of Germanic riven and rivet with their connotations of tearing and cutting. The tree diagram above shows the broader family, the relatives – Germanic and Latinate, the sprawling family lineage with all its twists and turns of the past, offering a diachronic perspective of the making of this family.

We have talked at length about belonging. We began the year inspired by Bouchra Khalili’s The Mapping Journey Project (2008–11) where short videos show the journeys of eight people forced by political circumstances to travel illegally through the Mediterranean area. Khalili invited each person to trace their journey in ‘thick permanent marker on a geopolitical map of the region’. We hear the subjects’ voices and watch only their hands marking their journeys across the map.

Our students recreated imovie maps of their stories and journeys until their arrival in Kuala Lumpur. We have been arrivals, some of us in many places, and understand the sense of dislocation, the longing at times for elsewhere, the slow movement towards belonging. And while we may miss family, friends from elsewhere, we know our families have chosen to move. We know nothing of the enforced departures of Bouchra Khalili’s subjects, nor have experienced the terror of fleeing for our lives as we have learned about in the texts we have read, the news programs we view, the stories we have heard from refugees in Malaysia.

Francesca Sanna’s haunting Journey was another powerful text shared in class reminding us of Tan’s statement that ‘the history of humanity is a history of migration under duress: of people leaving their life and home in search of a better life'(Sketches from a Nameless Land).

And so we meander towards arrival once again. Word investigation, the orthographic account and stories of word journeys, the arrivals into English, reflect more than the spelling of a word, more than the hypothesizing of the morphemes, more than a tracking of relatives. Words are artifacts and shine a light on humanity and moments in time. They help us reflect on the present. In the case of refugee and massacre we see the darker side of humanity that punishes difference, that persecutes and slaughters. In arrival we recognize the journey and hope of all those who leave an elsewhere and cross rivers or boundaries to touch shore in another place and try to make sense of an unfamiliar world, to belong.

For more on St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre listen to BBC In Our Time discussion of St Bartholomew Day Massacre and watch historian Barbara Diefendorf’s: Blood Wedding: The Saint Bartholomew’s Day Massacre in History and Memory where she discusses ’causes and implications of the 16th-century Saint Bartholomew’s Day Massacre of Protestants in France and the myth-making power of history.’

The richness of the discussions and trails you’ve laid out here for us to read creates a sense of longing and gratitude in me. I yearn to be back in junior high school, in Malaysia, in your Humanities class! And I am grateful that somewhere in the world, there are teachers like you who are deeply affecting their students’ minds, hearts, perceptions, perspectives and appreciation for shared humanity in such a positive and powerful way. This of course, leads back to a longing to back in junior high, in Malaysia, in your classroom with my own kids so we could all be gifted the opportunity to learn with you and your students. Thank you for sharing your experiences in this forum, you’re igniting sparks around the world!

LikeLike

Thankyou Lisa for reading this and commenting. It’s all in the word– what stories are reflected in a word! I cannot imagine not framing learning around a word- so often it’s the history of the world and the story of humanity. We continue our research and discussions. I love this shared discovery with my students.

LikeLike

Ann this is such a scholarly, yet easily understood, approach to the words used. Reading this is a journey in itself– in history and in etymology. Your post enables us to better understand civilisation and ourselves simply through a deepened understanding of the words we use. Your students are indeed fortunate to experience this depth.

LikeLike